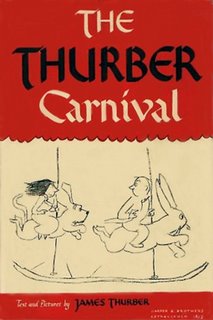

This was the first book I ever read. It was at the beginning of first grade, and I brought it to school with me because I was crazy about it. My teacher saw it and asked me about, and then I couldn't understand why she kept saying to all the other teachers, "Did you see this? She says she's read it." And they all looked at me ... strangely. Rather like some of the odd looks on the characters in James Thurber's drawings.

This was the first book I ever read. It was at the beginning of first grade, and I brought it to school with me because I was crazy about it. My teacher saw it and asked me about, and then I couldn't understand why she kept saying to all the other teachers, "Did you see this? She says she's read it." And they all looked at me ... strangely. Rather like some of the odd looks on the characters in James Thurber's drawings.Both of my parents loved it, too, and were constantly quoting bits to each other, so I got lots of exposure to it in varied context. I can't say I understood every aspect of it at that tender age, but I was fascinated by his drawings - the fierce women, the shy and frazzled men, the many dogs, strange rabbits, unicorns and "wire-haired fox terrier lawn dogs" that populated the Thurber world; simple drawings with enigmatic titles.

The stories were even more offbeat; some memoir of Thurber's life, some pure fantasy. The man who saw "The Unicorn In The Garden. "The Secret Life Of Walter Mitty." "If Grant Had Been Drinking At Appomattox."

Here's an excerpt from "The Car We Had To Push":

But to get back to the automobile. One of my happiest memories of it was when, in its eighth year, my brother Roy got together a great many articles from the kitchen, placed them in a square of canvas, and swung this under the car with a string attached to it so that, at a twitch, the canvas would give way and the steel and tin things would clatter to the street. This was a scheme of Roy's to frighten father, who had always expected the car might explode. It worked perfectly. That was twenty-five years ago, but it is one of the few things in my life I would like to live over again if I could. I don't suppose that I can, now. Roy twitched the string in the middle of a lovely afternoon, on Bryden Road near Eighteenth Street. Father had closed his eyes and, with his hat off, was enjoying a cool breeze. The clatter on the asphalt was tremendously effective: knives, forks, can-openers, pie pans, pot lids, biscuit-cutters, ladles, egg-beaters fell, beautifully together, in a lingering, clamant crash. "Stop the car!" shouted father. "I can't." Roy said. "The engine fell out." "God Almighty!" said father, who knew what that meant, or knew what it sounded as if it might mean.We can only imagine with what horror the Thurber grand-mère would have viewed today's wired and wireless world.

It ended unhappily, of course, because we finally had to drive back and pick up the stuff and even father knew the difference between the works of an automobile and the equipment of a pantry. My mother wouldn't have known, however, nor her mother. My mother, for instance, thought - or, rather, knew - that it was dangerous to drive an automobile without gasoline: it fried the valves, or something. "Now don't you dare drive all over town without gasoline!" she would say to us when we started off. Gasoline, oil and water were much the same to her, a fact that made her life both confusing and perilous. Her greatest dread, however, was the Victrola - we had a very early one, back in the "Come Josephine in My Flying Machine" days. She had an idea that the Victrola might blow up. It alarmed her, rather than reassured her, to explain that the phonograph was run neither by gasoline nor by electricity. She could only suppose that it was propelled by some newfangled and untested apparatus which was likely to let go at any minute, making us all the victims and martyrs of the wild-eyed Edison's dangerous experiments. The telephone she was comparatively at peace with, except, of course, during storms, when for some reason or other she always took the receiver off the hook and let it hang. She came naturally by her confused and groundless fears, for her own mother lived the latter years of her life in the horrible suspicion that electricity was dripping invisibly all over the house. It leaked, she contended, out of empty sockets of the wall switch had been left on. She would go around screwing in bulbs, and if they lighted up she would hastily and fearfully turn off the wall switch and go back to her Pearson's or Everybody's, happy in the satisfaction that she had stopped not only a costly but a dangerous leakage. Nothing could ever clear this up for her.

His stories were always so vivid to me, even as a kid. I reread them frequently, always with the same delight I had that first time. And I can still hear my parents quoting him.

Links:

Brief Thurber bio

Thurber's World (And Welcome To It)!

Thurber House

Thurber Stories, Links & Quotations

"The Dog That Bit People" (complete story)

4 comments:

"Well, What's Come Over You Suddenly?"

"Mamma Always Gets Sore and Spoils the Game for Everybody"

"For Heaven's Sake, Why Don't You go Outside and Trace Something?"

"Well, I'm Disenchanted, Too. We're All Disenchanted"

"There's no Use You Trying to Save Me, My Good Man"

To be a Thurber aficionado is also to be a dog lover; as such, one is sure to enjoy the man's illustrations for HOW TO RAISE A DOG: IN THE CITY AND IN THE SUBURBS, by veterinarians James R. Kinney and Ann Hunnicutt.

"Have You Seen My Pistol, Honeybun?"

"Well, It Makes A Difference To Me."

"I said 'The hounds of spring are on winter's traces, but let it pass, let it pass.'"

Post a Comment